In 1609, Henry Hudson explored what is now known as the Hudson River and Castle Island (now called Westerlo Island) which is where present-day Albany is located. Sometime between 1614 and 1615, the Dutch would erect Fort Nassau, a 12-man garrisoned trading post (or factorij) on Castle Island as it was a central hub of the beaver fur trade with Native Americans. This establishment consisted of a warehouse, an 18-foot moat and defended with two large cannons and eleven swivel guns.

Unfortunately for the Dutch, nature had other plans. Ice and snow melt during the 1617 spring thaw resulted in flood plains along the Hudson River to be inundated by water, and Fort Nassau was subsequently abandoned due to substantial damage. Within short order, and through the execution of their first treaty with the Five Confederated Nations of North American Indians, a new fort was established along the west bank of the river in the mouth of Norman’s Kill with the help of the Eelkens. This treaty would be renewed in 1645, and remain intact until the area was surrendered to the English in 1664. Nature, again, would have its way in the spring freshet of 1618 that subsequently destroyed the newly constructed fort.

That wasn’t the last of the Dutch, or their fur trade, though.

On June 3rd, 1621, the Dutch West India Trading Company (WIC) was granted a charter by the Dutch Republic with exclusive rights to West Africa and the Americas. Three years later, in May of 1624, Cornelius Jacobsen May, captain of the New Netherland, delivered the first group of thirty Dutch families, or Walloons. Eighteen men were sent to a location two miles north of where Fort Nassau had been erected - and repeatedly destroyed - where they established Fort Orange. The rest of the families went on to Governor’s Island which is where present-day New York City is located.

Forty-five more colonists would arrive in June of 1625 and dispersed, and by 1626 the use of African slaves was systemic. Although these ventures were chartered by the Dutch, most of the colonists were Roman Catholic Walloons (French speaking Belgians), French Protestant Huguenots, and enslaved Africans.

While Fort Nassau was the first Dutch settlement in North America, Fort Orange would become the first permanent one thus ushering in the Dutch colonial era with the realization of the New Netherland colony.

Because of Cornelius May’s role in establishing the New Netherland colony and transforming the territory into a broader province, he was declared the first Director of New Netherland and held this title from 1624 to 1625.

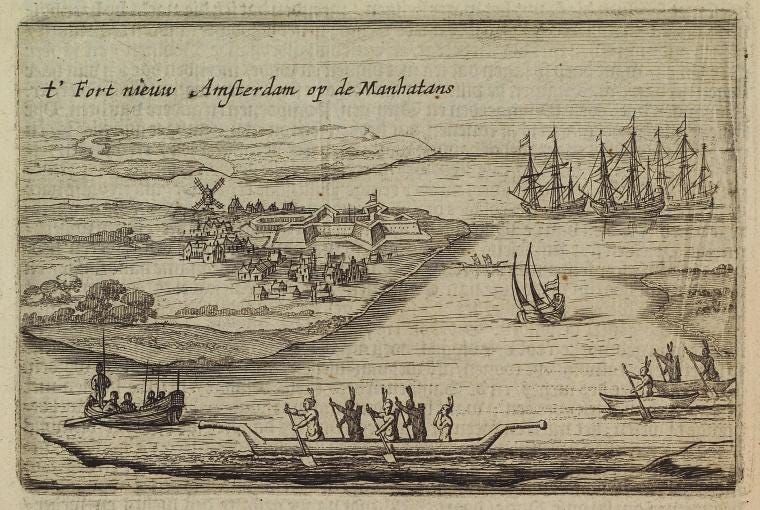

Among the forty-five new settlers that would arrive in the spring of 1625 was Willem Verhulst, who replaced May as the second director. Verhulst was not popular with the Dutch colonists, and as a result was replaced within less than two years by Peter Minuit who is widely understood to have overseen the purchase of Manhattan Island (then called Governor’s Island, although some historians argue that Verhulst is in fact responsible). Regardless, Verhulst is responsible for overseeing the decision to establish Fort Amsterdam on the southern tip of Manhattan Island.

New Amsterdam - modern day Manhattan - would become the first permanent European settlement, and later renamed as New York City in honor of the Duke of York.

The primary role of this newly established fort was to protect trading operations from English and French acquisitions along the Hudson River, and was the administrative headquarters of the Dutch.

A permanent Dutch settlement in 1625 did not just mean protection from competitors, enemies, Native Americans, and clearly nature. It also meant the formulation of a system of law and order. To be clear, the Dutch did not invent law and order. Native American tribes had long existed in North America before the arrival of Dutch traders, and colonists. Rather, the Dutch brought with them common law elements from Europe, and adapted to the circumstances for which they found themselves in.

Schout-fiscal’s, or schout’s (Dutch for bailiff), were appointed to deal with all manner of legal issues. By some measure, their duties combined what are in modern times duties that fall within the scope of sheriffs, magistrates, mayors, prosecutors, and aldermen, or rather, a one-man officer of both the enforcement of the law, and interpretation of the law.

With respect to the blossoming colony of New Netherland, the first appointed schout was in 1626, and the first appointment in New Amsterdam was not until 1652 when the Dutch granted permission for the settlement to establish its own government. During this time, the executive council would serve as the judiciary, where the appointed schout, while having a seat on the council, would step down and serve as a prosecutor. It is in this context that the modern prosecutor in America was born.

By 1628, there were approximately 300 settlers and slaves living in New Netherland with 270 living in New Amsterdam (the area around the Fort), and by 1650 there were between 800 and 1,000.

To be clear, the population was growing at an exponential rate. From 1655, there were more than 2,000 people in the grater colonial sprawl with more than 1,500 around the Fort, and by the time the Dutch surrendered in 1664 there were 2,500 in the surrounding area with nearly 9,000 in the broader province. Put another way, there was an average population growth rate of more than 72% per year, with a more than 2900% increase in the 40 years between the erection of Fort Orange in 1624, and the English acquisition in 1664.

It is within the context of rapid population growth that we see the birth of the Rattle Watch (or ratel wacht). In 1651, the governor appointed eight men and a supervisor, all of whom volunteered for the position, to patrol the streets. These individuals would carry long poles with lanterns that dangled from the top with green tinted glass. During this time, there were no street lights, and given that it was dark, the green lanterns were carried so that citizens could identify a patrolman easily.1

Rattle watchmen primarily did three things:

First, they served a means of deterrence. Their name derives from the fact that patrolmen would jangle keys on a ring, as making loud noises was often perceived as a way to deter would-be criminals from violating the law. They also had wooden rattles that they would use.

Second, they served as a means for people to report grievances to, after which the responsibility would be shifted over to the schout.

And third, they served as a sort of town crier as they would announce the hours between nine o'clock at night and the morning drum-beat. Often they would do this not just by yelling it on the street corners, but also by banging on doors and sheds. When the watchmen were done with their patrols, they would hang their lanterns by the door so as to show the citizens that there was still a watchman on duty, ever vigilant. This is why there are green lanterns permanently situated on precinct buildings in areas around Manhattan, New Jersey, and Albany.

In all, watchmen were given wooden rattles, keys, a musket, and a pole with a green lantern. If a watchmen needed assistance, they would spin their wooden hand-rattles which would function as a siren indicating to their peers elsewhere that they were in need of help.

Later, in August of 1658, the members of the rattle watch would begin to draw pay, and as a result, they became the first functional police force to be paid by what is now considered a municipal government.

Along with the rattle watch, the governor also requested two hundred and fifty leather fire buckets and hooks and ladders to deal with fires. By 1651, there were more than 120 wooden houses in New Amsterdam in close proximity, and as a result this was a significant safety concern. This was all paid for through taxation in the form of a beaver skin, or its equivalent.

The rattle watch was not particularly effective, and as we’ll see in future letters, there were systemic barriers to ensuring that the law was enforced. Issues related to rapid population growth, English control starting in 1664, various conflicts with Native American tribes, different religious beliefs, and increasing diversity would lead to substantial developments regarding how the law would be enforced in the northern colonies. Moreover, these issues don’t just shape events in New York and the establishment of the modern day New York Police Department, but also policing in America in general.

If you enjoyed this letter, consider subscribing. Doing so will mean that new content is sent directly to your email, in its entirety. Thank you for reading!